Column Buckling - Realistic Buckling Behaviour

![[object Object]](/_next/image?url=%2Fimages%2Fauthors%2Fsean_carroll.png&w=256&q=75)

In the first post in this series on Column Buckling, we introduced the fundamental ideas of equilibrium and stability. In the second post we expanded on these ideas to look at more realistic column structures with various support conditions and distributed stiffness.

In this final post in this series on Column Buckling, we’ll look at more realistic buckling behaviour you’re likely to observe in reality. In particular we’ll explore the behaviour of columns subject to eccentric axial load and columns with an initial deformation, i.e. columns that don’t start out straight.

1.0 Columns with eccentric axial load

So far we have assumed that all compression forces on a column are axial forces that have their line of action along the column’s longitudinal axis. As a result of this assumption the column will potentially experience the three states of equilibrium previously discussed:

- Stable equilibrium

- Neutral equilibrium

- Unstable equilibrium

However, in reality a column is not likely to experience such ideal conditions. Compression forces are often not axial forces but forces applied at some eccentricity from the column’s longitudinal axis. This results in quite different failure behaviour that we will investigate here.

1.1 Lateral deflection

We’ll set the analysis up by considering a column, pinned at both ends, but with an ‘outstand’ or cantilever protruding from each end. The cantilever is somewhat unrealistic but it simply serves here as a way of applying an eccentric compression force. The compression forces are applied at the ends of these cantilevers as shown below at an eccentricity, :

Fig 1. Column Buckling with eccentric compression force

The first thing we note is that the load applied an an eccentricity , is the same as simultaneously applying an axial load and a moment, ,

We can start by following the same procedure as before. We need to determine the differential equation of the deflection curve. We do this by evaluating the internal bending moment, at some distance along the height of the deflected column as shown in the right hand diagram above.

Now substituting this expression for into the differential equation of the deflection curve yields,

If we make the following substitutions,

We can express our differential equation as,

The solution of this equation follows very closely that of the fixed-free column discussed in the previous post. The general solution is given by,

We can apply the following boundary conditions:

Using these boundary conditions we find that,

and,

Which simplifies to,

The solution to the differential equation of the deflection curve is therefore,

We note that for a given value of and , the deflection is always defined. In the previous axially loaded column analyses we considered, we could only determine a buckling mode shape, but the maximum deflection, when , was undefined. This corresponded to a state of neutral equilibrium.

📌 From this we conclude that a column with eccentric compression forces has no neutral equilibrium state and therefore does not exhibit sudden column buckling behaviour.

1.2 Maximum deflection

For the pinned-pinned column considered in this case, the maximum lateral deflection, , occurs at the mid-height point, ,

So, evaluating our expression for at , gives,

After simplifying the expression we get,

Now, remembering that,

and that for a pinned-pinned column we know that,

we can rewrite ,

Therefore,

We can now substitute this expression back into our equation for the maximum deflection at the mid-height to yield,

We can plot this equation to obtain a load versus deflection curve for various values of load eccentricity, . This relationship is represented qualitatively below...

Fig 2. Column Buckling with eccentric compression force; Load versus maximum lateral deflection

📌 We can observe from this graph that the relationship between lateral deflection at mid-height and applied load is non-linear. This means we cannot use the principle of superposition to determine the influence of multiple simultaneously applied loads.

The vertical line in the graph above, represents the case when . In this case we observe the equilibrium states discussed previously. For values of , as approaches the critical load, the deflection increases and the horizontal line representing the value of critical load becomes an asymptote for the load-deflection curves.

Remember that the preceding derivation is based on the assumptions of small deflections. So in reality as the deflections increase, the observed behaviour of the column will deviate form the strict mathematically predicted behaviour visualised in the graph above.

💡A key takeaway from this discussion is that the behaviour of a real world column under realistic loading conditions is not likely to accord with the strict mathematical models we evaluated previously for perfectly axially loaded columns.

2.0 Columns with initial deformation

Now we’re going to consider the behaviour of a column that already has an initial lateral deformation. We will follow the same procedure as before to determine an equation that describes the shape of the column under axial load.

2.1 Governing differential equation

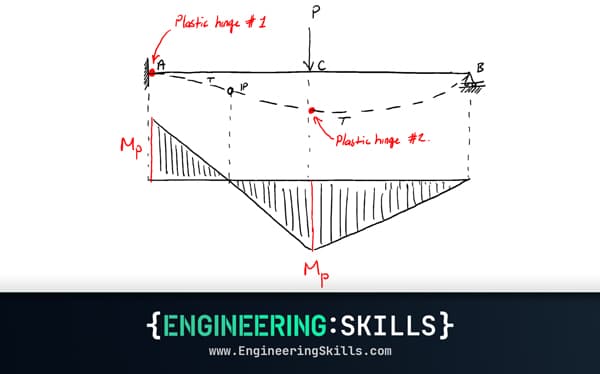

Consider the pinned-pinned column below that has an initial lateral deflection, :

Fig 3. Column Buckling: Column with an initial deformation

Note that the complete lateral deflection consists of the initial deflection and the buckled deflection:

By considering the equilibrium of a sub-section of the structure we can determine an equation for the internal moment of resistance at some position along the column length:

Fig 4. Column Buckling: Column with an initial deformation; Internal bending moment

Note that for clarity, hereafter we’ll dispense with the as it’s clear that the lateral deflection is always a function of . Taking moments about point A yields,

Substituting this expression for into the differential equation of the deflection curve yields,

Making the usual simplifying substitutions and letting,

and

we have,

To proceed with the derivation we need to assume some function of to describe the initial deformation of the column. For the purposes of this derivation we can assume that a simple sine function describes the initial deformation . In this case we have the following differential equation of the deflection curve,

We’ve already seen that the complementary solution (i.e. the solution when the RHS equals zero) is given by,

This just leaves the particular solution to be calculated. Because the right hand side of the differential equation contains a sinusoid, we can assume a general sinusoid for the particular solution, this gives us…

Remember that the reason we assume a solution is so that we can differentiate it and sub it back into our governing differential equation, so differentiating yields,

Now substituting these expressions back into our governing differential equation yields,

Now, if we equate cosine terms on the left hand side with cosine terms on the right hand side, we get,

Now since we know the term in brackets doesn’t equal zero, we can deduce that . Now equating sine terms on both sides gives us,

Rearranging this yields,

We can now state the particular solution to the equation as,

Combining the particular and complimentary solutions gives us the general solution,

2.2 General solution and boundary conditions

At this point we can apply boundary conditions to determine the remaining unknown constants of integration. At (base of the column at pin support), (the lateral deflection must equal zero). Imposing this condition on our general solution we find that . And so our general solution simplifies to,

The second boundary condition is that at (top of the column at pin support), (lateral deflection also zero). Again, imposing this condition yields,

From this we can deduce that must equal zero as the sine term cannot equal zero for a non-trivial solution. Therefore the complete buckling deflection is given by,

Now to make this a little easier to manage, remember that,

If we now define the ratio,

we can restate the buckling deflection as,

Therefore the total deflection (remember this is the initial deflection plus the buckling deflection) is given by,

We can simplify this to,

or,

where,

2.3 Observations

We can see from the equation derived above that the factor represents a magnification factor on the initial displacement. As the axial load, increases, the magnitude of lateral deflection increases but the deflected shape remains the same. Note that when , the equation breaks down as the magnification factor goes to infinity.

This is not likely to be a problem because is not likely to reach while the structure satisfies our small deflection assumption. We can plot the relationship between and to visualise the behaviour of the column.

Fig 5. Column Buckling: Column with an initial deformation: load versus deflection

It’s important to recognise that for a column with an initial deformation, we do not observe the strict mathematical column buckling behaviour predicted for perfectly loaded perfectly straight columns. Even so, the Euler load is still an important quantity that has a role in predicted the lateral deflection of the column via the ratio .

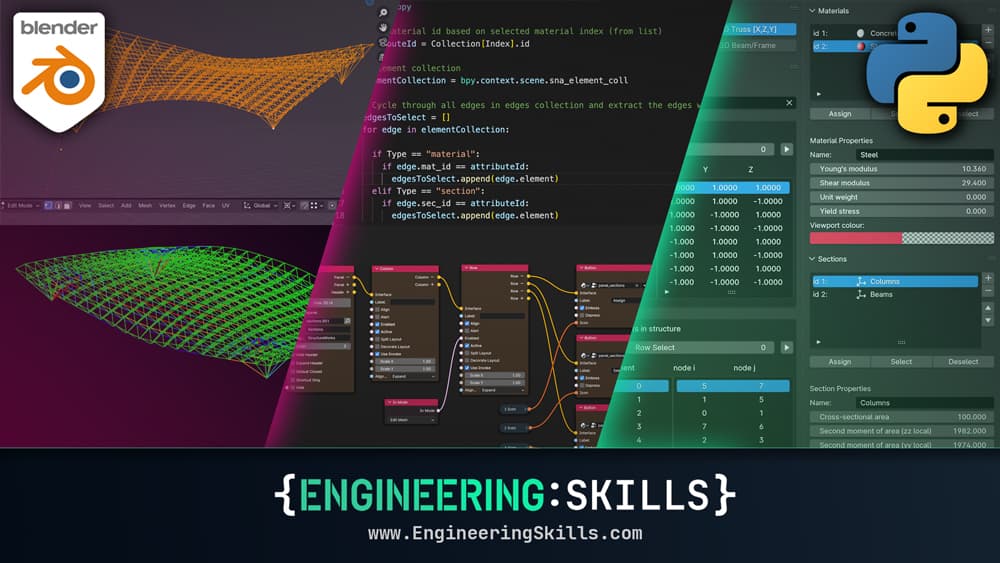

Dr Seán Carroll's latest courses.

Featured Tutorials and Guides

If you found this tutorial helpful, you might enjoy some of these other tutorials.

Finite Element Analysis and Structural Behaviour Modelling Case Study

Build an understanding of the structural behaviour of the Tintagel footbridge through finite element analysis

Dr Seán Carroll